Review: Solaris (Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh)

© Mihaela Bodlovic

Stanisław Lem's novel Solaris is one of the most famous tales to come out of the Cold War Soviet bloc, most famously being realised on film by Andrei Tarkovsky. Here it reaches another audience in a brand new play by David Greig, the Royal Lyceum Theatre's artistic director, and it's the best Greig play I've seen since The Suppliant Women in 2016.

The story dates from around the time of Yuri Gagarin's first manned space flight and looks far ahead to a time when humanity has sent a team of scientists to study a distant planet. All the action takes place on the lonely space station that's orbiting planet Solaris, manned only by Dr Sartorius and Dr Snow. When contact with the station is lost, Dr Kris Kelvin is sent to check up on them, but she discovers that encountering Solaris is having unexpected repercussions for the team, who have been receiving "visitors" from the planet. Sometimes these have been objects, but recently they have been images of loved ones. Slowly it dawns on them that the planet itself may be conscious and that it is trying to communicate with them. However, when Kris

is visited by the shade of her former lover, Ray, she puts her scientific objectivity aside and gets dangerously involved in the experiment.

Greig has taken Lem's novel (and bypassed the film) to create a neat distillation of the plot and ideas in a play that, including an interval, comes in at a snug two hours. That's an achievement in itself, and the many short scenes help to add to the characters' sense of dislocation and confusion. At the play's heart is the question of consciousness and – by extension – what makes us human. As Kris become empathetically embroiled in the experiment, Ray begins to demonstrate behaviour that is more human than they expect, raising questions about whether anything can become human, rather than it being an intrinsic state. And constantly on the fringes is the planet itself, a great seething brain that seems to tap into the humans' deepest feelings. Are they studying it, or is it studying them?

On another, more important level, however, the play is about something we can all understand: loneliness. These three (or is it four?) humans orbit an isolated planet in the farthest reaches of the galaxy. With only one another for company, they have a dysfunctional sort of community. But they're all isolated in their own conceptions, and the planet seems to know this. Kris' struggle to adapt to the return of her lost lover is particularly poignant because it taps into a sense of loss and regret that we all feel.

There are times when Greig's script paints unnecessary arrows around the story's message, but on the whole it's economically drawn and tightly organised. It's helped by Matthew Lutton's production, particularly Hyemi Shin's ultra-flexible set, which stays on just the right side of being an Ikea showroom. The stunning cinematography of Tov Belling and Katie Milwright is essential, as is the beautifully realised soundscape of Jethro Woodward.

Playing the three scientists, Polly Frame, Jade Ogugua and Fode Simbo embody three different psychological states of empathy – from disengagement and academic knowledge through to over-involvement – and Keegan Joyce brings an impressively broad range of emotions to the character of Ray.

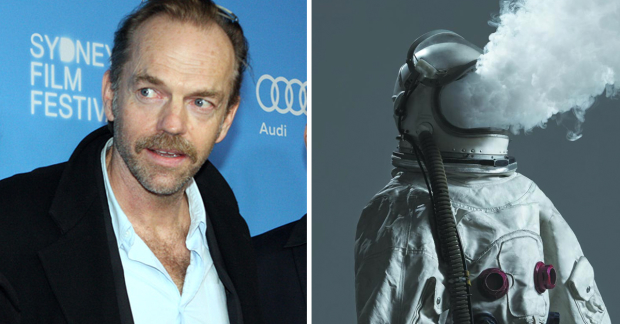

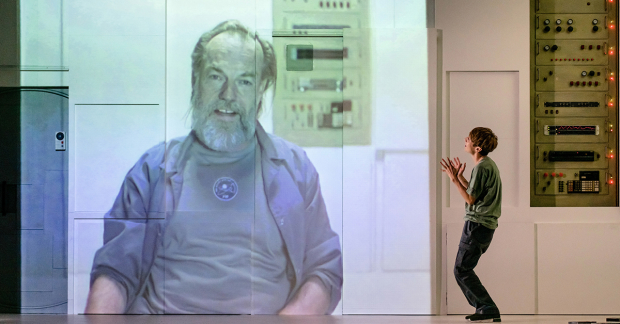

There's a fourth scientist too, however, played on video by Hugo Weaving. While he isn't there in person, in some ways his performance is the most compelling, talking to us from across the void and sharing his hopes and his fears about the planet they're studying. "It knows we're here", his video tells Kris: "Finally we're not alone". Worryingly, however, perhaps we finally are.