Manhunt at the Royal Court – review

Robert Icke’s world premiere production, marking his Royal Court debut, runs until 3 May

The impetus for a play about Raoul Moat who was, in July 2010, briefly Britain’s most wanted man, sprang from the then Prime Minister David Cameron’s characterisation of him as a “monster, pure and simple.”

The remark caught director and writer Robert Icke’s attention. In a world where it is all too easy to condemn, to divide people into evil and good, isn’t it the job of theatre to try to understand? To ask what we can learn from Moat’s journey from nightclub bouncer and tree surgeon to murderer. And whether that provides any insight into the troubling questions surrounding masculinity and its definition that have led to the rise of influencers such as Andrew Tate.

The result of such questions is Manhunt, a challenging piece that charts Moat’s life and its final acts: the shooting of his ex-partner’s boyfriend, her wounding and the blinding of a police officer while he went on the run for a week.

Like the Icke’s Oedipus which has just won the Olivier Award for Best Revival, Manhunt is sophisticated in structure and thought, and its treatment of its damaged protagonist is never less than interesting – people were locked in discussion long after it had finished. But in its attempts to be fair to both Moat’s tortured psychology and the suffering of his victims it doesn’t quite land as cogently and powerfully as you might hope.

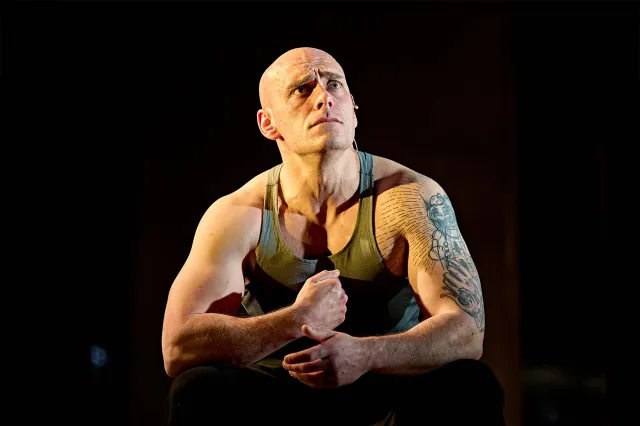

It begins brilliantly with Samuel Edward-Cook’s shaven-headed Moat pacing the stage, with a camera overhead beaming his every movement onto a front-screen, caught like a rat in a cage by his anger at his treatment by what he sees as a hostile society. “I feel tired, anxious, isolated, helpless, angry,” he confides to the disembodied voice of a therapist, listing an abusive childhood and stress among the reasons for his state.

On Hildegard Bechtler’s set, stainless steel beaten panels reflect Azusa Ono’s subtle light, imprisoning Moat in his thoughts; when he goes on the run through his beloved Northumberland countryside, they resemble a thundery sky. Characters come and go as if in a dream: his mentally ill mother promising him he will be a prince but locking him in his room; his younger self, fragile, longing to be a bigger man. Judges and barristers in an imaginary court, trying him for his offences; the police he believes are victimising him; Samantha, the woman he loves, but is violent – in a shockingly staged scene – towards.

There’s a sense of constant movement, underlined by a restless soundscape and incessant music, and video designs by Ash J Woodward that incorporate Moat’s text messages and Facebook posts. Although the scenes are invented, the words are his own, his rambling justifications of his actions, which circle back to his view of himself as misunderstood and wounded. Edward-Cook, muscled, hyper-active and glistening with sweat, brilliantly conveys his often frightening swings of mood.

Icke’s direction and command of an excellent cast playing many roles is disciplined and often audacious. In a long passage in darkness, we hear the story of PC David Rathband, blinded by Moat, who also committed suicide feeling his life had been destroyed by a random act falling from a clear blue sky. It’s utterly riveting but feels as if it belongs in a different play.

So does a revealing scene in which the footballer Paul Gascoigne (Trevor Fox) shares with Moat all his own feelings of inadequacy and despair over the definition of what it means to be a man; the point is that although Gascoigne did try to reach Moat, the police sent him back. Their fictional conversation is exactly the kind of therapeutic exchange that Moat needed to have yet could never countenance.

The idea that inside every big, strong, violent man is an injured boy “still wondering if anyone loves him” is emphasised by scenes that show the child Moat – dressed in the same orange T-shirt as the adult man on the run – grappling with the horrors of his childhood. Yet the damage caused doesn’t explain Moat’s actions. “Monsters often come disguised as victims,” says one of Moat’s accusers.

It’s in the final scenes that the play asks the key question: why is it only through violence that Moat can make people listen? Why as a society do we ignore the damaged men in our midst? But the message feels muffled. It’s a play fully of chewy ideas and superb commitment, yet its fidelity to the events on which it is based seems to prevent it from flaring into the brilliance it promises.