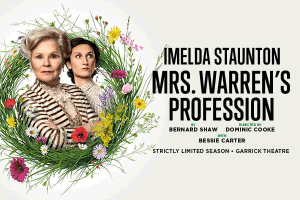

Mrs Warren’s Profession with Imelda Staunton and Bessie Carter – West End review

Dominic Cooke’s revival sees the real-life mother and daughter duo share the Garrick Theatre stage

Mother and daughter Imelda Staunton and Bessie Carter are playing Mrs Kitty Warren and her daughter Vivie in George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession. That’s the headline. The result is an extraordinary tour de force that brings the play to vivid and compelling life.

They look entirely different. The moment when Carter’s Vivie, highly educated, sophisticated and self-contained, looks wonderingly at Staunton’s Kitty, all compressed pragmatism, vulgarian life and unrefined vowels and asks: “Are you my mother?” is given all the more force by the fact that she towers above her.

Yet it is the quality that they share that powers the play, making its questions about morality and society fizz: both are remarkably good at using stillness and containment to suggest the most volcanic thoughts and feelings. In the two great confrontations between mother and daughter that shape the drama, the air between them seems charged.

The play is, famously, about prostitution and about Vivie’s shocking discovery that her comfortable life has been funded by her mother’s success in running a chain of brothels across Europe. The explicitness of this revelation meant that although it was written in 1893, it was deemed so “morally rotten” by the censor that it was only performed privately in 1902 and got its first public performance in 1925.

Of course, as Shaw argues in one of his lengthy prefaces to the first edition, it wasn’t so much the nature of the discussion that shocked his critics and the Lord Chamberlain, but the fact that he lays the blame for Mrs Warren’s choice so fiercely on a society that condemns working women to terrible poverty and puts them in the control of men who exploit and benefit from their work.

“Play Mrs Warren’s Profession to …women well experienced in Rescue, Temperance and Girls’ Club work and no moral panic will arise; every man and woman present will know that as long as poverty makes virtue hideous and the spare pocket-money of rich bachelordom makes vice dazzling, their daily hand-to-hand fight against prostitution…will be a losing one,” he writes. Or, as Mrs Warren puts it rather more simply: “The house in Brussels was… a much better place for a woman to be than the factory where my half-sister got poisoned.”

Both points could be made with equal force today and director and adaptor Dominic Cooke has shaved and sharpened Shaw’s original to make its theme of hypocrisy all the clearer. Everything has been pared away to shine the spotlight on the essential dilemmas, and to leave the audience to decide where outrage should lie.

To bring the debate into an even sharper focus, in a brilliant stroke, he has introduced a silent chorus of scantily-clad women who surround Vivie in silent contemplation, under Jon Clark’s piercing light. Their presence is a reminder of the human cost of the choices both women have made, the flesh beneath the mountain of words. The women gradually demolish Chloe Lamford’s simple, revolving set: it begins as a garden full of flowers, and ends as a bare, grey room. As a symbolic stripping away of illusions, it may be heavy-handed, but it is unbelievably effective in charting the play’s journey from sugar-coating to bare truth.

The greatest casualties in this barebones approach are the male characters – Robert Glenister’s blaggard Croft, the aristocrat who is in many ways the true villain of the piece, Reuben Joseph’s irresponsible Freddie, charming but pointless, Kevin Doyle’s panicked vicar, his ethics as fragile as his head the morning after a night of heavy drinking and Sid Sagar’s romantic philosopher, who prefers beauty to truth. Shaw gave them slightly more leeway than Cooke.

But the great virtue of the production is it allows the women to shine. Staunton’s Kitty is a close relation of her Mama Rose, monstrous in her own way, but more understandable and with more pathos. The little moue of her mouth as she speaks with bitter distaste of the poverty of her upbringing is hugely suggestive and invites compassion.

Yet for all Staunton’s command, it is Carter who drives the piece, charting with rigorous clarity Vivie’s journey from big-hearted, stuck-up innocent to a knowing woman who might just have a chance of making her own way in a world that will always be against her. She brings to the stage an honesty, a clarity of expression and thought.

In the final scene, Cooke sits them either side of a central desk to confront one another; Staunton’s Kitty is all agitation and reproach and as Vivie resists the full weight of her mother’s disapproval, Carter sits very straight and holds to her dignity. Her brilliance is that in doing so, she lets you see her sadness too. It is surprisingly upsetting.