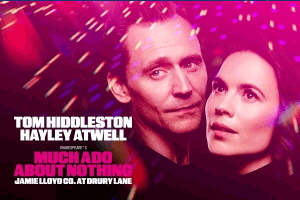

Much Ado About Nothing with Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell review – simply sublime Shakespeare

Jamie Lloyd directs a vivid and vibrant new take on Shakespeare’s comedy at Theatre Royal Drury Lane

It’s pink, it’s loud – and it’s irresistible. Jamie Lloyd’s new production of Shakespeare’s best-loved and richest comedy roars into Drury Lane on a wave of falling confetti and 1990s pop favourites, and lands with the force of a Marvel superhero.

It leans heavily into the star casting of Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell as Much Ado About Nothing’s bickering lovers Beatrice and Benedick. At one point, life-sized cut-out photographs of them in their most famous screen roles as Loki and Captain Carter are brought on stage. Yet the wit and depth of their portrayals owes little to their fame, and everything to their ability to take Shakespeare’s words and make them both truthful and incredibly funny today.

After the farrago of The Tempest starring Sigourney Weaver, this feels like an intelligent and uplifting return to form for Lloyd, who takes some huge decisions in his attitude to the play. He emphasises the party aspect of the plot, making the soldiers returning from battle to recuperate at the home of Leonato (Forbes Masson) swagger onto the stage like Top Gun heroes. There is a lot of dancing to songs performed by the excellent Mason Alexander Park, who plays Margaret, and wonderfully choreographed by Fabian Aloise to show the battle of the sexes that underlies the story.

Lloyd ruthlessly cuts the comic subplot featuring the bumbling Dogberry to focus entirely on the two love affairs – an old one between Beatrice and Benedick that both deny but which finally splutters back into life, and a new one between young Claudio and Leonato’s daughter Hero that flourishes until it is stopped in its tracks by a lie and a public shaming.

By upping the humour of the main strands (including using ludicrous heads of dogs, cats, ducks and clowns in the masked ball) and losing the (often tiresome) interludes of deliberate comedy, Lloyd emphasises the depth of Much Ado’s themes: the corrosive distrust between men and women in matters of the heart which both couples have to overcome.

Some of his staging is not just showy, but sensational. Both Benedick and Beatrice are tricked into declaring their love for each other by their friends, led by Gerald Kyd’s marvellously louche Prince, a man who hides his own strain of melancholy in carousing. Often, the matching scenes where they overhear their pride being criticised and the other’s merits praised, are remarkably similar in staging and effect.

Here Lloyd and his creative team have enormous fun with Hiddleston’s Benedick rushing around the stage, hiding under the piles of pink paper that cover Soutra Gilmour’s set, concealing himself behind a huge, red blow-up heart, and eventually falling down a hole, as his friends develop their plot. When it’s her turn, Atwell’s Beatrice stands stock still, listening to Margaret and Hero talking about her.

The expressions on Atwell’s face as she grasps the possibility that the man she loves might actually love her in return are a journey of discovery. Few actresses have her power to summon emotion and show thought, not just through her face, but in her entire body. She is clever, quick with the lines, but also completely in touch with her feelings. The moment when tears spring to her eyes when everyone is describing her as constantly “merry” reveals all the hurt and fear that lie beneath her brittle, battling exterior.

As for Hiddleston, he has the audience eating out of his hand. A lot of the action is played at the very front of the vast stage, and he brings the full weight of his charm and his impeccable timing to bear both on Beatrice and on the gallery. He weaves through the lines with revealing precision, finding lovely pauses between thoughts. “The Prince’s fool?” Pause. “Huh.” Laugh. The moment when he strips off his blue silk shirt to impress Beatrice with the rippling torso beneath is beautifully – and embarrassingly – played.

But most impressively both he and Atwell find the sombre strains and the deep feeling under the fun. When Hero is attacked by Claudio, it’s Benedick who plays conciliator, calming a furious Leonato as well as Beatrice, with gently outstretched hands. There are long moments of silence and quiet tension as he weighs up what to do and how to proceed. When everything turns out to be much ado about nothing, the joy of the couple’s final coming together attracts “ooh”s and “aah”s of sheer pleasure.

Even here, at the happy ending, Lloyd pays attention to the beats of the play. The maligned Hero (an unusually fierce Mara Huf) is allowed time to weigh up what to do by witnessing Claudio’s remorse; she gets to thump him before she falls into his arms. James Phoon registers a remarkable range of feeling at Claudio’s changes of heart.

The production is big, broad and for all its contemporary trimmings, absolutely Shakespearean in the way that it welcomes everyone into the entertainment. But it is also subtle, and very fine.