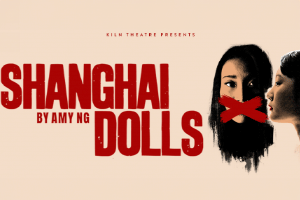

Shanghai Dolls at the Kiln Theatre – review

Amy Ng’s play, co-produced by Paines Plough, runs until 10 May

Amy Ng’s Shanghai Dolls has an original starting point. Two impoverished actresses meet at an audition for Ibsen’s A Doll’s House in 1935. One has her eyes fixed on stardom. The other is on the run from the Japanese who are invading China. They form a swift bond. “It will be us against the world.”

The encounter is based on a true story: the starstruck wannabe Lan Ping, who dreams of freedom, goes on to change her name to Jiang Qing and become Madam Mao, wife of Mao Zedong, and driving force of the Cultural Revolution, which killed millions. One of her victims was the other woman, Sun Weishi, adopted daughter of Premier Zhou Enlai, the first female theatre director in China.

The shifting relationship between them and the political upheavals and fervour that shaped their lives are the subject of the play that – rather like Robert Icke’s Manhunt, which also opened this week – attempts to explain the origins of Madam Mao’s evil, her transformation from glamorous actress to hardline zealot.

Ng is a historian by training and her writing is fluent, raising interesting questions of intent. Lan Ping is depicted as constantly, like Ibsen’s Nora, fighting to achieve self-realisation in a patriarchal society that pins her into boxes. Sun Weishi, daughter of a Communist martyr, has – ironically – initially more freedom to shape her destiny because she has power within the regime.

The problem is that though the theme is ambitious, Ng’s execution is constricted by being a two-hander drama that runs at just 90 minutes. Captions on faded sepia pictures flashed up on the back of designer Jean Chan’s barebones set, its shape defined by moving sets of doors, have to do an awful lot of the heavy lifting, providing a potted history of Chinese 20th-century history. At the end, we even see a glimpse of the real Madam Mao, in her own televised trial.

It feels too rushed, reducing the scenes between the two women to melodramatic statements of intent and great gobbets of plot. Under Katie Posner’s taut direction, it’s hard for Gabby Wong to find any nuance in Jian Qing’s onward journey into ferocity; Millicent Wong manages to make Sun Weishi more understandable as she grows from a scared 14-year-old girl into a much-loved director, but she remains a sketch.

The scene where – at her former friend’s instigation – she is tortured to death is depicted in vividly staged, convulsive movement courtesy of Annie-Lunnette Deakin Foster, with stark lighting by Aideen Malone. Nicola T. Chang’s score adds constantly shifting atmosphere.

But the play remains a frustrating experience, a tantalising glimpse of story that grips and fascinates but doesn’t quite deliver on its promise.